|

|

|

|

|

|

While the coach for athletes is prominent in the press, enjoying celebrity status, and a sizable income, the dancer's individual or company coach works quietly behind the scene. The first coach for the dancer may be the teacher, who sets the choreography for the June recital, the annual "The Nutcracker" or a variation for a competition. In a professional dance company, large or small, the ballet mistress or rehearsal personnel clean up the choreography, coach the group and understudies in the studio, during the pre-performance period. They are at best, enthusiastic, specific and can conduct a rehearsal with or without music, impersonal in making corrections and always available. They consult the choreographer when necessary but usually have a prodigious memory. Watching from a seat in an empty house during an onstage rehearsal, or during a performance, the ballet mistress or repétiteur (tutor, as they were once called) makes corrections immediately on stage or later at a rehearsal. They also take notes during a performance, and afterwards give individual corrections in the dressing room. Every moving eyeball is noted; every uncurled finger; every slack arm, raised shoulder or off-the-beat movement. Choreographic patterns are important. During a rehearsal, a correction may be as subtle as gently moving a young dancer's errant foot into a floor pattern, as the Russians do with the comment, "This is not done in our school." Corrections should not be taken personally and the dancer, without a studio mirror to self-correct on stage is unaware of errors, despite their development of peripheral vision and dimensional awareness. Coaching goes beyond the primary work of rehearsing steps and patterns and is concerned with musicality and the interpretation of a classical role, for instance, which takes the emphasis from patterns and steps to the level of interpretation and artistry. It is a slow, individual process and why European, some American companies, and major competitions have coaching sessions as part of their rehearsal schedule. It is a sensitive job requiring tact and authority. The Russians and a few other groups, before an actual studio rehearsal, have "table talk" sessions. The coach and solo artist sit at a table to discuss the interpretation of the role to be played, reaction to other characters, historical perspective, and how the character would walk onstage and leave still fully immersed in the role. Does this sound like a Stanislavski process based upon "dramatic truth"? Is is. Some productions of the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre Ballet came under the scrutiny of "the method," in the '20s and its influence continued into the '70s. Good dance coaches are rare beings, usually former principal dancers, who stay with their company after retirement, and make suggestions concerning the technical and emotional aspects of the role being rehearsed. Elena Tchernichova, an international coach, once remarked, "Coaches are born and not made." They are at best when they have no affiliation, preferences, personal or stylistic preferences, although many are known for coaching specific roles. They cost a fee and not every company's budget can afford one or even knows whom to hire. Coaches at competitions are especially important since, not knowing the contestant, they are more likely to be impartial. They make an important impression on the pre-professional dancer to develop new insight into a role; to do research in film libraries; and to find footage of different interpretations of their chosen role based upon different methodologies and eras. Some choreographers, as well, need a "third eye" advisor they can trust. Balanchine had Lincoln Kirstein, dour and almost inarticulate while watching rehearsals as his "third eye. "Mr. B," as he asked to be called, was the "third eye" for Jerome Robbins and other choreographers in the company. Dancers are sometime resistant to changes and persist in performing only in a way they are convinced their audience wants to see them: with high extensions, in multiple turns, using a flirtatious manner with the audience. Foolish is the dancer who is not willing to try a new approach to an old role and to lose her mannerisms. "They do what they want," is the coach's frequent complaint. A professional dancer's day consists of morning class, rehearsals and seven weekly performances in which they may or not perform or be an understudy watching in the wings. A young dancer once remarked to Margot Fonteyn that it was all "hard." "Then why are you doing it?" she responded.

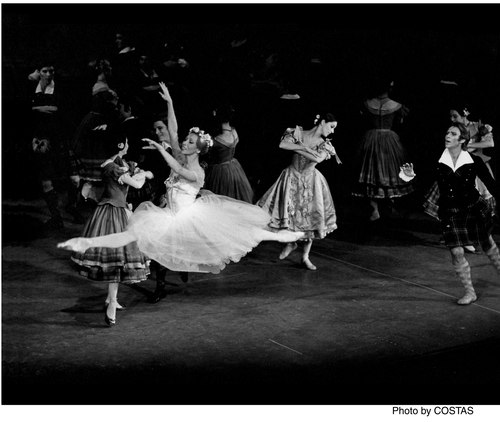

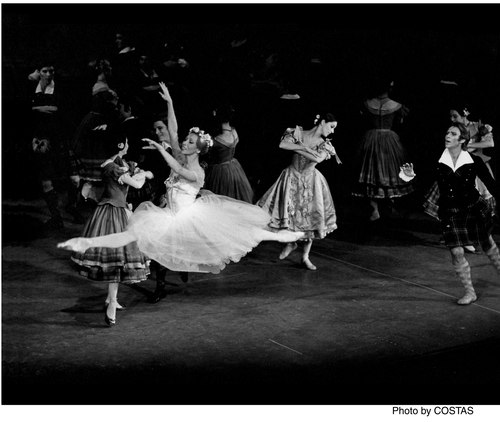

Natalia Makarova and Ivan Nagy, in American Ballet Theater's "La Sylphide"

Makarova has frequently coached and staged classics.

Photo © & courtesy of Costas |

|

|

|